(english below)

In Bangladesch leben knapp eine Million geflüchtete Rohingya in großen Lagern im Südosten des Landes. Solange der Bürgerkrieg in Myanmar weitergeht und auch die Gefahr eines weiteren Genozids an ihnen noch besteht, können sie nicht zurück. Diese Situation dauert nun schon viele Jahre an und die bisherige Regierung hat wenig getan, um langfristige Lösungen für die Geflüchteten zu finden. So läuft vor Ort eine der größten humanitären Hilfeeinsätze der Welt, um die Geflüchteten mit dem nötigsten zu versorgen. Mit angesetzten Neuwahlen nach der Revolte der Studierenden in Bangladesch ist unklar, wie es jetzt weitergeht - die Übergangsregierung hat bisher keine Vorschläge unterbreitet und so sieht es momentan nach einem weiter so aus. Ein Redakteur von Radio Corax war vor Ort um sich die Lage anzuschauen, und aus dem erlebten wird klar wie kompliziert die Lage ist - doch diese Geschichte beginnt nicht in den Lagern selbst, sondern in einem Café in einer der Großstädte von Bangladesch.

(english)

No End in Sight

In Bangladesh, almost one million Rohingya refugees live in large camps in the south-east of the country. As long as the civil war in Myanmar continues and there is still a risk of further genocide against them, they will not be able to return. This situation has been going on for many years now and the previous government has done little to find long-term solutions for the refugees. One of the largest humanitarian aid operations in the world is currently underway to provide the refugees with the basic necessities. With new elections scheduled after the student revolt in Bangladesh, it is unclear what will happen next - the interim government has not yet made any proposals and so it currently looks like things will continue as they are. An editor from Radio Corax was on the ground to take a look at the situation, and from what he experienced it is clear how complicated the situation is - but this story does not begin in the camps themselves, but in a café in one of Bangladesh's major cities.

Transcript

Linn Khant: "No rohingya student is allowed to study here in bangladesh so I'm a masquarading as a bangladeshi so that nobody can identify me"

In a coffee shop - one of many outlets of the same middle class chain - I meet Linn Khant just after prayer time. We are in one of the larger cities of Bangladesh, where it took me an astonishingly long time to reach our meeting place through some of the worst traffic in the world.

Linn Khant actually has a different name, and he is one of the few rohingya refugees in bangladesh enrolled in one of the universities of the country - even though Rohingya are not allowed to be students there. His illegal attempt to gain higher education is extremely risky, but if you listen to the way the former government presented itself as the saviour of the rohingya people from a genocide in their home in Myanmar, which borders the southasian country to the east, it isn't quite clear why exactly this is such a risk.

Mohammad Arafat: "We are also the victim of genocide. If you go back to the history of the way this country was born in 1971, 3 million people were killed, brutally killed.

So you always have the sensitivity and sympathy, a soft corner for the people who are victim. And that's the reason why. Without having any pressure from anywhere, we voluntarily opened our border. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina did that, and she was recognized as the mother of humanity because of doing that. We are trying our best to accommodate them\Nwith all the kind of things they need. And many people in our country itself actually were opposed to this idea, So, that's my point, we also do not want them to go back and\Npotentially facing again another genocide. So, that's not what I'm suggesting at all.

That is the well-worded position of the former Minister of state for information and broadcasting, Mohammad Arafat, which he gave in February 2024. His government - the Awami League - shaped the current situation drastically, as they had been in power since 2008, until they were toppled by student protests against increasing authoritarian tendencies and social inequality in July and August this year. In contrast to this promise of Mohammad Arafat, that they had accomodated the Rohingya refugges with all the things they need, Linn Khant had to fake his identity, pretending to be Bangladeshi, to persue his studies at the university - this has to due with the fact, that the rohingya refugees have been pretty much confined to large camps with only temporary infrastructure in place, as the Bangladeshi government intends to send them back to Myanmar, to repatriate them, as quickly as possible. That this will be possible anytime in the future is very unlikely. The strict muslim rohingya people have faced persecution by the buddhist majority in Myanmar for many decades, the first refugees arriving in Bangladesh in the 70s, with larger waves fleeing the country during military crackdowns in 1978, 1991 and 1992, in 2012, 2015 and in particular from 2016 to 2018. As Linn khant recounts, the Rohingya people have no allies in Myanmar that haven't historically turned on them - as he demonstrates with the example of the National League for Democracy, which won the elections in Myanmar in 2015 with support of the Rohingya population that had been promised an end to discrimination. The National League for Democracy then allowed the military crackdown and genocide of the rohingya in 2017 to happen - an atrocity during which most of the refugees now in Bangladesh fled from Myanmar.

Linn Khant: "You know our people believed the National League for Democracy before they came to power, we gathered support for them. But what they did after coming to power they also removed our people they also caused harm on people once they came to power. They always betray us, every party in Myanmar, they betrayed the rohingya people. Once they gain power, once they achieve their goal they turn on us."

This makes it extremely unlikely that even if the current civil war in Myanmar is over, that the Rohingya can just return to their home in Rakhine State in Myanmar. This raises the question, how the policy of Bangladesh towards the Refugees should actually be, under the assumption that they won't return anytime in the near future. Pressed on this matter, the former Minister of state for Information and Broadcasting, Mohammad Arafat, dissembles.

Mohammad Arafat: "Well, I still don't believe that, I don't think that there's no way to, for them to go back. I believe that they should go back. And actually, they also want to go back. But the problem is, it is not possible at this moment, and they don't get any, uh, you know, the proper, uh, you know, the citizens right if they go back. So we are waiting for that time. And when it comes to the integration of the system in our country, it's really, really difficult. As I said, we're already overburdened with lots of people. So I think that here again, I believe the international world, the global, the western world and the developed countries with small population and big, uh, chunk of land. They're, they have lots of things to do. I think Bangladesh has done enough. So, how about the rest of the world? They should take, take care of some of the, you know, the burden, I believe. What I'm saying is if we can actually push the Myanmar government, all of us together and make sure that they create an environment where after going back they feel genuinely they feel safe and a safer environment can be actually provided. And then when they voluntarily wants to go back. This is what I am emphasizing on. We don't want to push them to go back and face with another genocide. That's not our position."

The policy of the former government, which had been in place for decades, is quite clear: They are ready to maintain the refugee camps, but their goal is to get the Rohingya out of Bangladesh again as soon as it is geopolitically possible. It is quite unlikely that the new government that is currently being formed after the student revolts this summer, will change their stance on this issue, at least there are no signs in this regard so far. This is a real problem, as the support that the refugees are really getting, is a lot worse than the rehearsed phrases of government spokepersons make it seem. For example, the Rohingya Refugees are legally not allowed to work in Bangladesh. This means they can't get work permits and earn money, and also bars them from the Bangladeshi education system - two things that Linn Khant explains, are the most pressing needs of Rohingya like him.

Linn Khant: "If our people are given the right to education and the right to earn livelihoods, you know it will add a great value to the country's GDP as well and at the same time the crisis will be lessened inside the refugee camps"

The refugee camps for the Rohingya, all within a relatively small area in the south east of the country in Cox Bazaar, which is better known for it's beach resorts, and on the island of Bhasan Char, are supported by a huge humanitarian aid effort through the United Nations, which has also reacted to this need, as Kun Li, who works at the Bangladesh country office of the World Food Program in Bangladesh mentions during a visit to the camps.

Kun Li: "So that is there, you know, every refugee forum, you know, high-level refugee meeting on Rohingya, that's the UN's repeated message, please allow them to make a living for themselves."

So if work and education are limited to the small scope of whats officially allowed within the camp system, what always happens, no matter where in the world, is that people find a way to pursue their goals anyway - especially in a country where legal restrictions are less facts of life and more a matter of having the right connections and paying bribes.

Linn Khant: "You know most of our people are willing to learn but they are scared of being arrested, they are scared of termination. You know earning an education in Bangladesh is an impossible thing, well not quite impossible but you are not sure of anything. You know the education that the bangladesh students are getting they are certain that they if they continue they keep their consistency they will be graduated one day, but for our people this is different, that even if they keep their consistency if they're caught they will be terminated. It's an uncertain task for our community, but i'm assured that there are a lot of people who are willing to learn who are willing to liberate themselves from that kind of slavery."

Remember the word "terminated" that Linn Khant uses here, while he refers to the risks of illegally gaining an education, like he is quite successfully doing. But before we return to Linn Khant's story, we have to understand the specific situation, the reasons why these policies are in place - that the Rohingya are kept in a perpetual limbo of uncertainity for the past few years.

Since 2021, a civil war is raging in Myanmar, just a few kilometers away from the refugee camps in Cox Bazaar in Bangladesh. The Arakan Army - one of the rebel groups in Myanmar, is actively fighting there against Myanmars Military Junta, with quite some success. The journalist Arif Reza, who is based in Bangladeshs capital of Dhaka, already foresaw them effectively controlling the area by this summer, when we met in Dhaka in February 2024.

Arif Reza: "The Burma situation is going very interesting. The Arakan Army, I think, will take over the capital within three or four months. They will take it. The Rakhine capital, not the Burma capital."

And the following months showed him right. As the NGO Crisis Group reports, the Arakan Army has defacto taken control of the region as of August 2024, pushing back the military Junta effectively - and, as the report also mentions, have begun discriminating against Rohingya extensively in their proto-state, which is also the homeland of the Rohingya who have largely fled to Bangladesh. The government of Bangladesh has been wary of any spill overs from that war, but can't effectively prevent small groups crossing the jungle border and smuggling materials to Myanmar and drugs out of Myanmar through Bangladesh, drugs, with which the war itself is being financed.

On top of that, Bangladesh has it's own issues, as is quite evident in the fact that a student lead revolt just forced a change in government this summer -the former Minister of state for information and broadcasting, Mohhamad Arafat, described the difficulties of the present quite well, just before being pushed out of office.

Mohammad Arafat: "Well, this is, uh, definitely, it's very difficult for a country like Bangladesh. We already have lots of people here. The most densely populated country in the world. And we have to take care of these people, 170 million people. On the top of this, when you see that, uh, like more than a million people coming into Bangladesh and, uh, we have to take care of them too. And also they're increasing in numbers. So it's making it really difficult for us. And the local people are also getting affected big time because of this."

The economic effects of over 960 000 refugees in the camps are severe, especially since the government also has to tackle a poverty level of 70% among the Bangladeshi population. Thus it's no wonder, that they aim to return the Rohingya refugees as soon as possible. During our discussion in Dhaka, the journalist Arif Reza also observed, that the local sentiments towards the presence of the Rohingya refugees is a problem.

Azif Reza: "The Rohingya are very poor, low income generation people, and they are basically speaks in same language of our Chittagong, but they have different alphabet. So, the people knocking on Rohingya are the poor people. It is a general sentiment. So, it's a problem. But outside of country, from Dhaka, from Gachari, from Pune, they are watching this like aerial view. So, they think Rohingya is a political problem. They are blaming the government. The government cannot send them. What are you doing? They are thinking on that. They are thinking the government has failed to negotiate with Myanmar. There are diplomatic mistakes or other mistakes. The government did not raise voice so firmly. So, this problem is not being solved. So, they are blaming government. They have no interest with whether Rohingya is threat, Rohingya is friend or how this problem can be solved. They have no interest, actually. It's a problem. But, I have another observation. In Rohingya camp, there are many jobs of Bengali NGOs.

There are many NGOs involved in this Rohingya management. Many NGOs. These NGOs get from West, and the NGO has big employment for mostly Bengali, and it gives high salaries. So, this Rohingya actually created job market in Cox's Bazar and Dhaka NGO sector."

The support for the Refugees, as well as their needs have stimulated the local economy. This is also an observation that Martin Rensch shares, he is the Press Officer for the World Food Program, which provides large portions of the food for the Rohingya refugees in the camps.

Martin Rentsch: "Which also strengthens the local economy. Here it is relatively small, because these are these aggregation centers, they bring the fresh stuff in from outside, that is sold, but for example in many other refugee situations the refugees then also go to local supermarkets and buy it there and if the Syrian refugee brings me money, then I am more inclined to accept it."

These more general observations don't quite reflect the reality of life as a Rohingya refugee, as the things Linn Khant has experienced show. Over a cup of coffee he told me about his life, and although he has escaped the refugee camps to study in a university, his life has been shaped by these factors, for he was born in the camps shortly before the new millenium after his parents fled from Myanmar in 1992. His father left early on, heading to Saudi Arabia to find work with which to support his four sons. He is also one of the main reasons why Linn Khant persued an education.

Linn Khant: "I was born there and you know things were a little bit normal. My father had some consciousness to make us educated and that's why he went to saudi arabia with the aim that he would be able to make us educated. I was a kid then and then when my father used to talk to us you know he always instructed us to study, to make us educated and once we are educated we would be able to have the freedom that we lost and we will be able to do anything we want in life. That's how he inspired us and beside that we have an relative who was staying in the refugee camps with us and he was a teacher so we got some inspiration from him"

In his memory, the lack of the right to work and to get an education play a prominent role, as well as the fact that it was forbidden for them to leave the camps.

Linn Khant: "We were kind of locked in and if we had to go out we always had to go secretly, like you know going to the hospital. Then you needed to have permission otherwise if you were caught, nobody will really speak for you and you'll have to manage by your own and you probably also have to pay bribes. We always had to pay bribes."

For a while, Linn Khant lived in the refugee camp and went to a national school, masquarading as a Bengali student and hoping that no one would notice. Sneaking out of the camps on a regular basis was only possible, due to the help, that some of the Bangladeshi people in the neighborhood provided. At the same time it was essential to hide what he was doing from those who would attempt to reveal their actions to the authorities or earn some money by threatening to reveal them. Today, at the university where he is now studying, this hasn't changed - a constant fear that someone might find out and he'd be discovered. This way of life is quite common for those families living in the camps - Linn Khant's brothers have to hide their identity at their respective workplaces to keep his job. Together they collectively support the family.

Linn Khant: "We are very close to our families and we share everything with our family members. And our family lives in Cox Bazaar and they are somehow managing the family, maintaining the family's expenditures. But it's quite uncertain all the time, as they are masquerading as Bengali. So that's how they are maintaining and they are surviving."

The difficulty in gaining not just jobs, but also a good education that his family has experienced, is also one of the driving reasons for Rohingya to also want to return to their homeland - in the hope of gaining easier access to all these possibilities, to taking control of their own lives again. This is expressed in the response that many refugees give when asked about their hopes for the future, just as Sufaira, a rohingya refugee woman, who teaches mothers how to feed their children in camp 15, examplifies.

Translator: "Actually she wants to go back to Myanmar because if they stay here they cannot educate their children and they cannot have land for gardening or agriculture."

Kun Li, who works for the World Food Program, has also experienced how widespread this ultimate wish to return is.

Kun Li: "There are some days when they commemorate when the influx sometime in August. That's when you know that the influx came from Myanmar.

And the message is we want to go home."

Linn Khant, never having been to the rohingya homeland, also wishes to return there some day. He has also been struggling to achieve a good education all his life - and his story takes a dark turn several times. Most recently, he was arrested for illegaly studying just five days before taking the exams that would allow him to go to university. Somehow police officers had found out that he wasn't really a Bengali student.

Linn Khant: "At night they came to my apartment and then I was taken into custody at three a.m in the morning and then they came in the morning and they were asking for money and they said that you know once you give the money we will release you and they were initially asking for a big amount and then we negotiated. After negotiating to four thousand taka I managed to get that from some of our relatives and what we had saved up, that's how I managed and then I was released on the same day. It's all about the money, nothing else, it's horrible and if you fail to give them the money then you will have to face the worst of it. It was only days away from my final examination and I was in a hurry that I have to get out of this at any cost because if I failed to sit for that examination I didn't know if I would be able to do it in the next year and I cried a lot in front of them and I said to them that you know you have sons you have brothers like us you know I was not doing anything wrong here I was just studying, I'm not running any criminal activities, so that's how I tried to convince them and they were convinced finally with the money. I changed the apartment right after coming back from their custody, that's just a precaution, because you know they also instructed us to change the apartment".

Had he not been able to secure a release by paying the police officers out, he would have missed the exam, where his good grades then allowed him to study at a university in one of the larger cities of Bangladesh. Obviously, the money he had to pay was a bribe, no court proceedings followed, and he also wasn't brought back to the refugee camps. But this hadn't been the first such experience in the few years of school. When Linn Khant was in 10 Grade, he endured a much harder trial.

Linn Khant: "So my families were still there in the camp and I was in school only six kilometers from the refugee camp, and when i was in class 10 i was arrested, because i was a rohingya refugee, by the police. They took me to a the outskirts of a forest, the police took me there and then they were demanding money and initially they were asking for a huge amount of money that i couldn't have never you know imagined so i said that you know i'm just a refugee and and you see how our situation is and how do you expect that i would be able to pay you the ransom. He said that no you will be able to pay because your people are dealing with drugs and you must have the money. But i said that if you have any single proof that we are engaged with any kind of drug deals or anything like that, then i will give you all the rights to do anything you want to me and he said that no I don't need anything else you just give me the money and then I will release you."

What followed was a lengthy ordeal. The police took Linn Khant into custody for four days and he was repeatedly beaten, with the pressure, to somehow pay a ransom for which he couldn't have the money, never letting down. He remembers there having been three rooms for the prisoners. In one room they kept all those people who would be sent to prison, the second one was for those, that were being held to pay a ransom. Linn Khant was in the third room, and the other prisoners explained to him what he should expect.

Linn Khant: "There were also other people who were asking me why I was here and I said that I don't know and that I didn't know what was going to happen to me next. They said that this is the room for the people who'd be shot. They were going to shoot me. Without any reason, if you cannot fulfill their demands for money. These people were going to be shot to death because they did not fulfill the ransom demand of the police"

At the time, just a few years after Sheikh Hasina and the Awrami League had won the elections and taken over the government, there was a relative high number of such extra judicial killings. Linn Khant knew at the time of a record high of extra judical killings by the police - he remembers the number of 204. His turn to be taken away by the police officers did come soon.

Linn Khant: "They covered my head with a black cloth and then they were making sounds with a gun and they were telling me that you know, you have the very last chance to survive, if you fulfill our demand we will release you. I said that I will never be able to pay the amount they were asking for and i'm ready to embrace the death but i cannot afford the money that they were asking. They were arguing with me and that continued for 30 to 40 minutes and they were telling me that we decreased the amount and started negotiating, saying that I was lying, and if I don't pay, they would kill me and that nobody would speak about it because I was a rohingya and they could easily kill me. I continued to tell them, that I really don't have the money and that they should go ahead and kill me."

After this horrible torture had gone on and on, Linn Khant got lucky. The police officers finally brought him back to the cell. But the next day the beatings and extortion continued. After four days, they had reduced the sum enough, that he deemed it possible to borrow enough money to pay them, and Linn Khant was given a phone to contact his family to organize the payout. For them, organizing the sum was extremely difficult. His dad, who worked in Saudi Arabia as an illegal immigrant, didn't earn enough money in two years to pay for the ransom. In the end, his family and their neighbors all pooled toegether the ransom of 10 lakhs, roughly 900 Euros. With the money payed, the police sent him directly to prison, instead of releasing him, where he had to await a trial before a court. For the trial the police invented the charge, that he had cut down 153 trees in the forest. As this charge agains a teenager was quite obviously absurd, the court decided to release him on bail instead of keeping him in prison, but still the extortion wasn't over.

Linn Khant: "So I went to the police to submit my bail paper and the police again asked for a money so that they would countersign the bail paper, and then i somehow managed that money too and then i gave it to them,sothat I wouldn't have to present myself at the police station every month for the one year bail duration. It was really tough."

In the end, Linn Khant had payed over 3000 Euros in bribes, endured four days of torture, including a mock execution, barely eluded becoming the next termination victim in a spree of extra-judicial killings, and all that, while he was in 10th Grade and just because he dared to go to a normal Bangladeshi school as a rohingya refugee.

The right to work and an education, that the refugees demand, is not just about allowing them to earn their own livelihoods - it's also about ensuring that they can live without fear of such experiences, because they can't survive without work and an education, so no matter if it's illegal or not, they have to try anyway or face a life teetering on the brink of starvation with no perspective of change. This becomes obvious, when faced with the reality of life in the camps.

Aid Worker: "In Cox's Bazaar, there are 33 camps and another camp is in Bhasan Char. In the whole Cox's Bazaar camp, there are around 3,400 learning centers.

And in this whole learning centers, there are about 248,000 learners. So in Camp 15, there are 248 learning centers and around 24,000 children in this Camp 15 only."

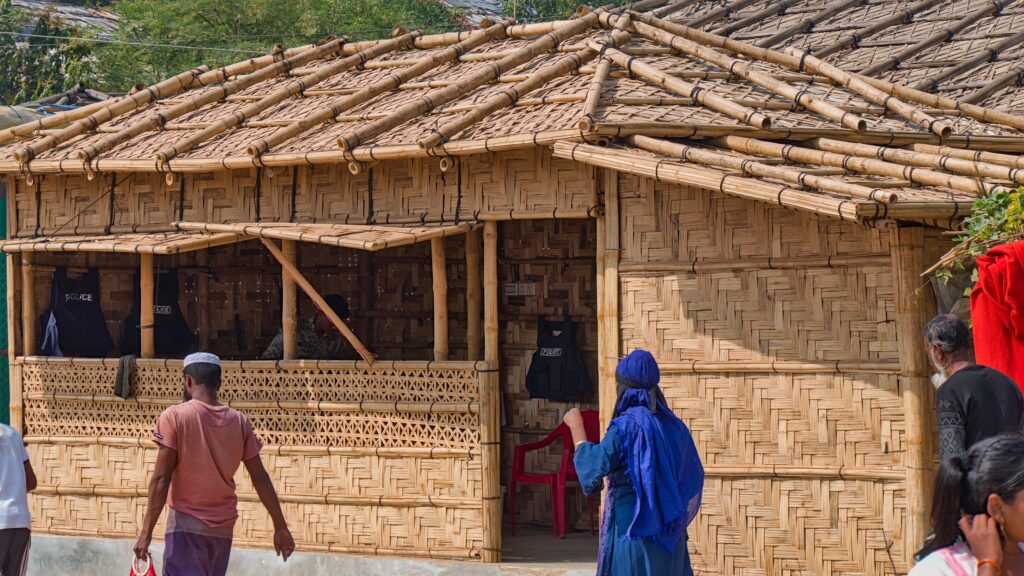

The aid worker who is describing how the aid programm is attempting to provide basic education here, stands in the middle of one such learning center. Three shacks, filled with children who are being instructed by a teacher, stand around a central courtyard.

Aid Worker: "And in each learning center, there are two teachers. One is from Bangladesh community and another is from Burmese. So, the Bangla teacher is called Bangla teacher and the Rohingya teacher is called Burmese instructor. So, these two teachers manage one school and these are the students."

All of the buildings in these learning centers are built from basic materials, the floor is packed dirt, the walls and roofs are made of bamboo. As all structures, with rare exceptions, they are not allowed to be built with concrete, since the camps are meant to be temporary by government decree - even though the Kutupalung Refugee Camp has existed since 1991. The World Food Programm is also engaged with the learning centers - which officially can't be called schools, as that would also imply that the camps aren't temporary - to provide nutrition in the form of buiscuits for the children, which are fortified with vital vitamins and minerals as well proteins, as most children here suffer from malnourishment.

Aid Worker: "Including providing these fortified biscuits, we generally promote hand washing, cleanliness, awareness raising, these kind of activities. And we have also tried to get enough funds to provide cook meal as well. But hopefully, someday we will be able to do that."

Obviously, the learning centers aren't only about providing better nutrition for the vulnerable children, they are mainly implemented for educating the children, as Rushad Islam, a Field Officer in the Emergency Education Program run by Young Power in Social Action and Save the Children, makes clear.

Rushad Islam: "We are trying our best to ensure access to basic education children have the basic right to get an education."

Between these huts, the assembled staff explain, that 70% of the children in the camp recieve an education, based on the Myanmar curriculum, for grades 1 to 5, where they learn Burmese, Math, Life skills, social studies and science, and as Rushad Islam makes sure to point out, they also learn to show respect towards each other and to live in dignity.

But the grading system has only been in place for a year now, just a few years ago, people like Linn Khant wouldn't have profited from these learning centers, so there is a gap in education between the first families arriving in the camps over thirty years ago, and when the learning centers were established - but not only that, after fifth grade, there has so far also not been a possibility for continuing their education, as the UN is just now implementing grades six to ten. On top of no real path towards education having existed here in the past, the choice of a Burmese curriculum is also based on the premise of the Rohingya returning to Myanmar soon. And while Linn Khant and his brothers were always pushed towards an education, this hasn't been the case for girls so far - even though the classes present at the learning center seem to be well mixed.

Rushad Islam: "We're working to motivate the caregivers and parents on importance of girls education. We are trying to convey the message that education, this is one of the basic rights, so that girls also have the right to get education."

For the fact is, that many parents don't believe that their daughters need an education - they will after all be married of in an arranged match at an early age, and before that, they're of more use at home, a mentality that Shariah, who works for the WFP in Bangladesh, points out.

Shariah: "They need to be working, They try to keep there children at home, they do not allow there children to come to school."

And when girls are allowed to get an education, the parents will make sure that they stop going to school as soon as they reach puberty, due to the religious beliefs of the muslim rohingya community. At the learning center, the male aid workers expressed their conviction that it had gotten easier for girls to get an education, and that parents take pride in this nowadays, but their female colleague, described the situation in more guarded terms.

Teacher: "Quite honestly speaking, it's very difficult, for educating girls in this community, but we are hopeful, people are changing actually so we are hopeful that we engaged more girls in this area."

So what remains of the promise of education is a basic level for grades one to five, with higher education until ten slowly coming now - over thirty years after the camp came into existence, and depending on your gender the likelihood of getting some education varies greatly. Leaving the camps to visit other schools is forbidden, and also very dangerous, as Linn Khant's experience makes quit clear - but for him, an education is the essential first step towards allowing the Rohingya to help themselves.

Linn Khant: "All I think is that if they, you know, convince the government to give the right of education to the Rohingya, I think this will help a lot more than the food rations. If they are able have an education without restriction, things will change in 10 years or 15 years. It will radically change."

The changes that would be possible through education are also reflected in the teachers positive view on the change happening in regard to girls education.

Teacher: "They're changing, and it's a positive change, that's very good."

This is the last impression that stays with me upon leaving the learning center and returning to the bustling footpaths and streets of the refugee camp, where a market has materialized during my stay in the center.

The refugee Sufaira, who herself works as a teacher for expecting mothers, recounts, that, as her husband doesn't have a job, he goes fishing in the Bay of Bengal to make ends meet and provide for his family - even though it is forbidden for the Rohingya to just take up jobs in Bangladesh. Still, there are employement opportunities in the refugee camps themselves, but they pay badly and come with severe limitations, even though the aim of the project has good intentions.

Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi: "So the purpose of setting up the upcycling center, So first of all, to provide the income opportunity among the refugees. The second point is develop the skills for the refugee. And then the third point is environmental friendly and also the waste management. So what we do..."

As Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi, program policy officer of the WFP Cox Bazaar Resilience Unit, explains at the Upcyclying Center, there are jobs for collecting packaging materials from the food supplies, and for creating new products like bags, from these discarded materials. Environment friendly, and also connected to teaching the necessary skills for producing household items. In one room, a group of maybe 30 women are sitting in front of sewing machines and creating the fabrics out of the waste material. But the work they get here has some government mandated restrictions.

Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi: "They can work for 90 days at a stretch. After 90 days, we select the new beneficiaries. We go to the door-to-door, to their houses, and we explain the activities, what we are going to do. If they are interested, then we say them, "Yes, you can come." And if not, actually, we also try to motivate them, "These skills here is your portable skills. "You can do it here, and if repatriation happens, "then you can use these skills in your country also." So they come to the centre every day from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. for seven hours a day, 50 taka per hour, 350 taka per day."

350 Taka per day, that's equivelant to 2 Euros and just over 60 cents, which roughly 200 people of the 50 000 in this part of the camp can earn at any given time at this one upcycling center - and just as a side note, here the Aid Worker speaks of repatriation as a possibility, not as a guarantee. After the 90 days though, they have to leave this job. Some can then use the learned skills to do small contract work amongst their neighbors. They can't return to the center and work again at a later date, unless they get hired to train newcomers.

Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi: "But our criteria is that the women is the priority. And also person with disabilities are also is there. Because we cannot train the 50,000 people because they are different ages. Other than 18 plus years, we cannot involve them any work actually. This is restricted from the Bangladesh government actually."

The scope of these kind of income generating projects thus has a severely limited impact, it is no wonder then, that many of the refugees, like Sufaira's husband, are dependent on finding work elsewhere - even if it's not legal.

Something that I also noticed directly in front of the Upcycling Center in the refugee camp was a blue box, a letterbox, that had the word "complaints" written on it, and the complaints that the Aid NGOs receive show how basic the problems that the Rohingya refugees face daily are.

Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi: "So in a sense, not that much of complaints we receive. Sometimes they receive, they don't get food on time. Sometimes they lose their ID cards,

Sometimes they said, "I want to eat, you can say, meat, but I am getting some vegetables."

The complaints that Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi lists here are followed up on and the refugees are informed of how the problems then get adressed, while more sensitive issues are handled in a more elaborate procedure, if investigations and more extensive discussions are required. The issue of securing enough food to survive appears to be a driving factor though, even with food security for the refugees being a central part of the UN Aid effort apart from providing shelter. Food is provided at outlet stores in all of the camps, where dry food rations - rice and chili being the main ingredients - as well as fresh vegetables are sold.

Guide: "Well uh so here inside you can see all are the dry ration here basically we separated dry ration and very fresh vegetable item that is two separate shop here inside within this shop all the dry rations are here there are about 12 to 14 items inside the shop and from this area people can buy whatever they want how much quantity they want they can shop here and then if very vegetable there need to visit the other shop as well onion here we have oil and it's a red lentil here sugar."

The idea is simple: Refugees get a voucher worth a certain amount and can buy those goods they want to have, from the selection provided. Problematic is, that the amount they get varies, depending on how well the UN aid response gets funded by the international community. In 2024, the ration had to be reduced by one third for a few months due to shortfalls in international funding. The scarcity and forced reductions have also left a lasting impression on Linn Khant.

Linn Khant: "Nothing has increased, it was almost the same, we had to struggle to have food in our mouths. The money, the ration that they used to provide us it's like you know we could hardly survive for 10 days to 15 days. After that what we used to do once our ration was done is that once our father sent us money we used to buy something so that we can eat and then if he cannot manage then we had to borrow from other neighbors. This is how the community is built up, you borrow from others, the other one will borrow from you. It's a cycle. Everybody was struggling really hard to have their own living."

What the Rohingya have experienced in the last years, is that they have to help each other and that they can't depend on unconditional help - instead their networks to those, who have left, provide support, with those who are connected to refugees who have found work elsewhere profiting most if those individuals manage to earn enough to afford to support their families in the camps.

Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi: "And then, but there's some of the problem, which is the dietary diversity, and also the nutritious food for Rohingya people. So in this sense, we established to the aggregation center, which aiming to the fresh food supply to the refugee camp as much as possible. So there are three objectives of the aggregation center, market linkage from the local community to the refugee camp..."

Apart from providing food on a basic level, nutritional variety is also a problem - as Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi, the program policy officer of the WFP Cox Bazaar Resilience Unit explains during a visit to a local community near the camps. A problem that the NGOs providing Aid also adress, while at the same time offering the local communities opportunities to earn money by providing fresh vegetables and fruit to the Rohingya Refugees - another project that is not yet at its full potential and just started three years ago. The food the local communities can provide though, isn't cheaper than imported food.

Kiyomichi Mitsukoshi: "No, no, no, so why do we challenge to this kind? Make a social cohesion, right?"

Social cohesion, which helps to alleviate tensions between the local host communities and the 960 000 Rohingya Refugees that they have as neighbors and which are sharing the land with them for several years now. As a member of the local sales center states, they now don't have to bring their produce to a faraway market and even get better prices for the food they grow.

A member of the aggregation center speaks Banga.

The food rations aren't enough, and the produce sold at markets for the refugees also only help, where they can afford to buy enough of them. As a result, malnutrition is a constant problem in the Rohingya refugee camps. Children who show signs of malnutrition get direct help in specific centers in the camps, run by the WFP and UNICEF.

Aid Worker: "So here the volunteers go door to door in every month and screen all the child from the 6 to 59 months as well as pregnant and lactating women to screen the malnutrition. If they found any malnutrition cases they are directly referred to the nutrition facilities available in that area. So later on they get services from this nutrition site."

These facilities are life-saving, for the acute malnutrition rate among the 150 000 children under the age of five in the camps is 15 percent, with 2 percent being severely malnourished. In light of this situation, it is no wonder that education and thereby finding work are such central goals of the Rohingya refugees, even though most of them only want to be able to return to their homes - this struggle for survival though is also influenced directly by another factor, the security situation in and around the camps, which stands in stark contrast to the touristy beaches and nightlife of the Cox Bazaar coastline not far from the refugee camps.

Linn Khant: "You see my my entire family is out of the camp. They are living in secret in a town outside the camps because they are no longer safe in the camp because we were we were attacked by groups inside the camp and we complained to the police, but they are not taking any kind of productive steps to make us protected. My uncle the camp leader, the refugee representative for multiple times because he was kind of educated and he was kind of popular in the camp and people trusted him. He had the communication with the officials and if any kind of investigative reporters come to the camp they used to communicate with him And the drug groups thought that he used to leak information about them. This is why we were attacked by them. These groups, they do drug deals and run drug activities and they abduct people and ask for ransom, that's how they were operating. That's what they were initially doing. And they are comprised of both Rohingya and Bengal people, so right now we can't go back to the camps. I cannot even visit the camp because of my security issues I miss the place that I was born, but I cannot go there to visit."

What Linn Khant has experienced here, are the consequences of the Rohingya Solidarity Organization, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army and the Nabi Hossain Group operating in the camps and in Cox Bazaar in general. They traffick a form of Methamphetamine, which is called Yaba locally, from Myanmar to India, where the drug reaches it's clandestine international distribution networks and these organizations abduct people for ransom payments - in short organized crime in all it's variety, within the context of a large and sprawling refugee camp and a complicated border situation with a civil war on the other side. All three groups fight over control of the markets in the camps, where they extort protection fees, leading to Rohingya like Linn Khant also having quite strong opinions about them.

Linn Khant: "The Rohingya Solidarity Organization and the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, they are both comprised of the rohingyas yet they are fighting against one another. There is no systematic reason to it, they are not organized, they are not systematic they don't have a roadmap. They are keeping our people in conflict against our own selves. If there is an internal conflict, they leak information to the Police and Military of Bangladesh, and they go and arrest members of the respective groups. It's like brother against brother."

At the same time, both organizations also profess to fight for the Freedom of the Rohingya in their Homeland in Myanmar - which gets complicated quickly, for ARSA, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, are the alleged perpetrators of an attack on a Myanmar military Outpost in 2017 which some observers say caused the 2017 Genocide in Myanmar - this would make them partly if not directly responsible for what most of the refugees currently in the camps had to endure. The claim to fight for an independent Rakhine state for the Rohingyas is what ARSA and RSO, the Rohingya Solidarity Organization, have in common: a fight for the rights of the Rohingyas, but both have devolved to criminal groups that also extort their fellow Rohingyas - while the Nabi Hossain Group is clearly a drug gang lead by Nabi Hossain, who was arrested in early september. In regard to ARSA and the RSO, as always with insurgent groups, the politics involved are murky. Linn Khant is sure, that ARSA is actually two groups - not just one.

Linn Khant: "There are two divided groups of ARSA, one is going for the fight and another one is running the illegal activities inside the camp. But these are fake ARSA, these are not the real ARSA. The real ones are fighting, they are in the forest, they are still in Myanmar. The Things that the media is showing inside the camp, they are fake ARSA, they are running illegal activities with an intent to make money, to cause harm on others. They have no intent for revolution. They are fake ARSA and that's why people are sometimes confused."

From an outside perspective, it is hard to get a clear picture of the facts - but for the Rohingya refugees the infighting and organized crime is an everyday struggle that they have to navigate, for while the aid workers have a fixed policy of leaving the camps before dark, the Rohingya can't so easily avoid dealing with the drug groups and extortion gangs, all of which just adds more problems on top of the questions of survival on limited food, without good access to education and work.

In light of this situation, it is no wonder that the right to an education and to work outside of the camps are so central in discussions amongst aid workers and amongst the Rohingya themselves. And they have become more and more pressing, as the years drag on, for the good intentions of the people of Bangladesh, to help the Rohingya who are facing a genocide in Myanmar, have begun to fray. It is not without reason, that Kiyomishi Mitsukoshi from the WFP, addressed the social cohesion between the refugee communities and the local host communities as one aim of the project to provide fresh produce through the local market. Just as the former Minister of the government talked about having open arms in 2017, Linn Khant experienced the same openess, but this attitude has shifted, an observation where he reinforces the view that the journalist Azif Reza also expressed, wherein the Bengali people have come to view the Rohingya as a problem.

Linn Khant: "Yeah, it has changed. The way our people were embraced in 2017, they came with whatever they had to support vulnerable people so that they can survive. But over time, through the disinformation of the media, it has changed. It has now become that, we will, you know, we will seize their land. So the host community, the rural people of Cox's Bazaar really think that one day the Rohingya will demand the land of Cox's Bazaar over time and they will be in a conflict. That's what they say. The truth is different. You know, in every community there are good people and bad people, but you cannot say that all the people are bad. They are temporarily staying here, but they will go back once their land is safe."

The former government, which was deposed by a student revolt in the summer of 2024, had reacted to these fears with a clear message of aiming to send the Rohingya back to Myanmar, and relocating the refugees in Cox Bazaar to an isolated island in the Bay of Bengal, goals that the former Minister Mohammad Arafat expressed quite clearly.

Mohammad Arafat: "I mean, this question is absolutely absurd of integrating and learning and all that. They are being taught their language, their curriculum is being followed for the next generation and all that. Because I mean, if you accept it, that, uh, To integrate them into our country. Then, uh, many other countries, Myanmar will also be encouraged. They would want to push, push back more, or push in more people into Bangladesh. It's not going to be a good idea. So, Bangladesh government, as of now, in principle, they have no plan, such plan to integrate these people into our country, into our system. And they should, they also deserve to go back to their own homeland, right? They should not be going in in some other country, even though if you integrate, they'll always feel in generations that they're not from here. It's not a good idea."

The responsibility to provide a situation where they can go back - that lies with the international community, according to the former minister of state for information and broadcasting. During our conversation he even envisaged Canada or Australia accepting Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh, as they have so much more land and fewer people. Linn Khant also sees an important - but decidedly contrary role - to be played by the international community.

Linn Khant: "You know, if the US strongly holds the government of Bangladesh accountable for the right of education for the Rohingya, Bangladesh will be, forced to give the rights to the Rohingya for education. If the international community does that, yes. Just the local aid agencies, they don't have that power. The international community should play their role here."

With this whole situation in mind, and talking to local aid workers, it isn't hard to read between the lines when they discuss the situation - but no one will directly challenge the government position officially, as international humanitarian organizations don't want to be seen as influencing the internal politics of any country.

Aid Worker: "Currently, government doesn't like that they go outside of the camp and work. This is a political will. If actually people, the leaders of two countries or our countries actually wishes to allow, then they can, otherwise cannot. We want that, we want that they should be, some scope should be there. Scope should be there to work actually."

In light of the current situation though, people like Linn Khant are making their own opportunities, even if it means breaking the law every day. And the path Linn Khant has chosen, to enroll in a university while pretending to be from Bangladesh, is also in service to his hope for a different solution to the situation of the Rohingya. He choose to study journalism, so that he can learn how to motivate people to free themselves, as he tells me in the clean urban coffee shop high up in a skyscraper of one of bangladeshs larger cities, far removed from the dirt packed paths and bamboo huts of the refugee camps.

The path he has chosen is difficult, not just because he could be discovered at any time, but also because he can't stay at a university dormitory. If he did, someone could notice him communicating with his family - risking his exposure. So he needs to rent a place to stay. This obviously requires that he also has to work, when he isn't studying, to pay his bills as well as support his family.

Linn Khant: "I want to do something for my people, because in our community nobody is publishing our stories. So I want to write our own stories, I want to write our own sufferings, I want to educate and I want to persuade our people so that they can go back to their land. I really want to publish stories of what's real, honest, authentic, but to liberate people, to persuade people for a great cause, for a positive cause. Our people are really dying. You can also kill people with illiteracy. You can also kill people with hunger. So our people are facing all those situations for over 30 years now, 33 years now. So what's left?"

And this is where his solution begins - slowly - to take shape. For it is his belief, that that without their land, the Rohingya will never have freedom, even if they are granted citizenship in Myanmar, they would still be marginalized. In his eyes, if they would have the land themselves, then they would be able to live there in their own way, following their own strict muslim customs. And as pretty much every Rohingya in the camps, he too wants his people to return to their land.

Linn Khant: "Ever since I have been hearing the same word, that doing a repatriation will happen, but I'm in mymid twenties, it still has not happened, it will never ever happen without any armed struggle and it should come from our community, because we want our rights. Nobody will go to fight for us, we have to fight for ourselves and without an armed struggle we can never have our land back. But we are not united, we have to be unified first and we have to have that kind of understanding that there is a conspiracy going on against us, it's against the repatriation and it's against the whole community and they don't want to end the Rohingya crisis."

An armed struggle, that would add to the chaos of the civil war in Myanmar, where the Rohingya won't be able to rely on any allies, as the Arakan Army, which now controls their homelands has repeatedly turned against them, just as the myanmar military has as well. An armed struggle that would also further add to the death toll of the gruesome war in Myanmar, in the hopes of finally allowing the Rohingya to live as free people in their own communities. There are no easy answers, no obvious bright futures to strive for, where the 960 000 refugee Rohingya who have fled from Myanmar over the past 30 years to Bangladesh are concerned. What is clear, is that the current situation is a stop-gap solution, a temporary fix, that in its state of permenance means the loss of dignity and liberty for nearly one million people, every day. Maybe the change in the government of Bangladesh that is currently taking place offers new perspectives, but so far support for them or new ideas have so far been lacking in any meaningful discussions on the future politics of the state, as new elections are prepared. What we do know, is that the previous regime of Sheikh Hasina had just begun to implement an alternative to the refugee camps near the border, an alternative, where the Rohingya get a better education, access to work, and permanent buildings to live in. The only catch is, that this refugee city is built on an isolated island in the Bay of Bengal, called Bhasan Char, where nobody else lives - reducing the risk of the Rohingya and Bangladesh communities mixing. A scheme, that also sounds like a permanent prison for the forseeable future, and another dead end in regard of an actual solution. In the meantime, the refugees continue to struggle on, one day after another.

Author: Aljoscha Hartmann

Unsere Arbeit ist nur dank eurer Unterstützung möglich. Wir freuen uns immer über Spenden oder Fördermitgliedschaften. Noch besser ist es natürlich, wenn ihr Lust habt selber Radio zu gestalten und freies Radio nicht nur hört und unterstützt, sondern auch macht! Gerne könnte ihr uns jederzeit Feedback geben.